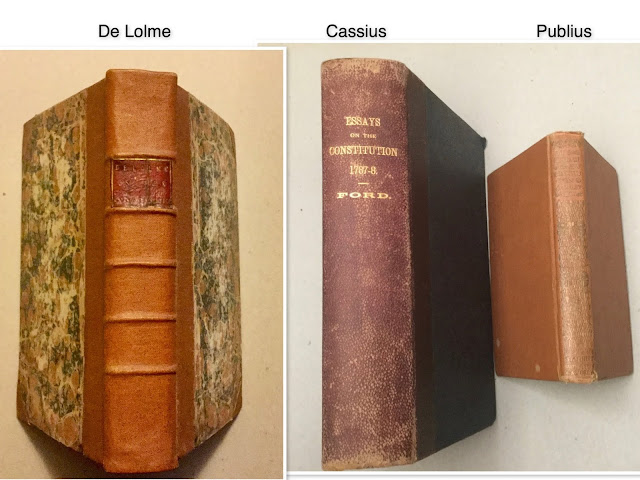

With the current interest and yes, disinterest, in the topic of impeachment, I decided to open the pages of three books on Constitutions in my library. I wanted to see what our forefathers might have been thinking regarding impeachment when the Constitution of the United States was being discussed in 1787 and 1788.

The Constitution of England by J. L. De Lolme was first published in Amsterdam in French in 1771. De Lolme was born in Geneva, but had to emigrate to England because one of his political writings upset the leaders of Geneva. An enlarged English edition of his book was first published in London in 1775, with new editions in 1777, 1781, 1784, 1800 and several more afterwards. Elbridge Gerry, Benjamin Franklin, and Thomas Jefferson had copies of De Lolme's book on the Constituion. Elbridge Gerry was a member of the Constitutional Convention in 1787, but refused to sign the United States Constitution because it did not contain a Bill of Rights.

The following paragraphs were extracted from the 1800 edition of The Constitution of England. The words in each paragraph were identical to those printed in the 1777, 1781, and 1784 editions.

... But who shall be the judges to decide in such a cause? What tribunal will flatter itself that it can give an impartial decision, when it shall see, appearing at its bar, the government itself is the accused, and the representatives of the people are the accusers?*In a note De Lolme recalled that the Earl of Danby pleaded the king's pardon during his impeachment in 1678. It caused such a ruckus that parliament was dissolved. A law was since enacted which said "that no pardon under the great seal can be pleaded in bar to an impeachment by the house of commons."

It is before the house of peers that the law has directed the commons to carry their accusation; that is, before judges, whose dignity, on one hand, renders them independent, and who, on the other, have a great honour to support in that awful function, where they have all the nation for spectators of their conduct.

When the impeachment is brought to the lords, they commonly order the person accused to be imprisoned. On the day appointed, the deputies of the house of commons, with the person impeached, make their appearance: the impeachment is read in his presence; counsel are allowed him, as well as time to prepare for his defence; and at the expiration of this term, the trial goes on from day to day, with open doors, and every thing is communicated in print to the public.

But whatever advantage the law grants to the person impeached for his justification, it is from the intrinsic merits of his conduct that he must draw his arguments and proofs. It would be of no service to him, in order to justify a criminal conduct, to allege the commands of the sovereign; or, pleading guilty, to produce the royal pardon*. It is against the administration itself that the impeachment is carried on; it should therefore by no means interfere: the king can neither stop not suspend its course, but is forced to behold, as an inactive spectator, the discovery of the share which he himself have had in the illegal proceedings of his servants, and to hear his own sentence in the condemnation of his ministers.

An admirable expedient! which, by removing and punishing corrupt ministers, affords the immediate remedy for the evils of the state, and strongly marks out the bounds within which power ought to be confined: which takes away the scandal of guilt and authority united, and calms the people by a great and awful act of justice: an expedient, in this respect, so highly useful, that it is to the want of the like that Machiavel attributes the ruin of his republic (92-94)....

In 1888 Paul Leicester Ford's Historical Printing Club published a collection of Pamphlets on the Constitution of the United States Published During its Discussion by the People 1787-1788. The reception the book received proved that the writings were only neglected because they were unknown. In 1892, his Historical Printing Club published Essays on the Constitution of the United States Published During its Discussion by the People 1787-1788. Ford reasoned that since the Federalist made the essays that were published in the newspapers of New York City popular, his book would make the essays that were published in the newspapers of other cities popular as well.

One of the essays in Ford's book was written by a lawyer and politician who wrote under the pseudonym of Cassius.

THE MASSACHUSETTS GAZETTE

Friday, December 21, 1787

For the Massachusetts Gazette.

To the Inhabitants of this State.

(Continued from our last)

Section 1 of article II. further provides, That the president shall, previous to his entering upon the duties of his office, take the following oath or affirmation: I do solemnly swear ( or affirm) That I will faithfully execute the office of president of the United States, and will, to the best of my ability, preserve, protect, and defend the constitution of the United States. Thus we see that instead of the president's being vested with all the powers of a monarch, as has been asserted, that he is under the immediate controul of the constitution, which if he should presume to deviate from, he would be immediately arrested in his career and summoned to answer for his conduct before a federal court, where strict justice and equity would undoubtedly preside....Cassius, it turns out, was James Sullivan (1744-1808). Sullivan shared John Hancock's political views, and Hancock rewarded him by appointing him the Attorney General of Massachusetts in 1790. Sullivan would later succeed Hancock as Governor. On a side note, Elbridge Gerry unsuccessfully ran against both Hancock and Sullivan, but finally became governor in 1810.

Section 4, of article II. says, The president, vice-president, and all civil officers of the United States, shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of reason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.––Thus we see that no office, however exalted, can protect the miscreant, who dares invade the liberties of his country, or countenance in his crimes the impious villain who sacrilegiously attempts to trample upon the rights of freemen.

Who will be absurd enough to affirm, that the section alluded to, does not sufficiently prove that the federal convention have formed a government which provides that we shall be ruled by laws and not men? No, surely but an anti-federalist (38,39)....

The Federalist was first published in 1788 in New York by J. and A. McLean. It is No. 519 of Everyman's Library series, was first published in the series in 1911, and was reprinted twelve times. My copy was reprinted in 1917. The Federalist contains 85 essays, most of which first appeared in the newspapers of New York City. Alexander Hamilton, John Jay and James Madison all wrote under the pseudonym Publius, and sought to persuade the people of the State of New York to adopt the Constitution. Alexander Hamilton was the author of Federalist No. LXV.

From the New York Packet, Friday, March 7, 1788

THE FEDERALIST. No. LXV (Hamilton)

To the People of the State of New York:

The remaining powers which the plan of the convention allots to the Senate, in a distinct capacity, are comprised in their participation with the executive in the appointment to office, and in their judicial character as a court for the trial of impeachments. As in the business of appointments the executive will be the principal agent, the provisions relating to it will most properly be discussed in the examination of that department. We will, therefore, conclude this head with a view of the judicial character fo the Senate.On a side note, which is an end note as well, Alexander Hamilton cites De Lolme in The Federalist LXX.

A well-constituted court for the trial of impeachments is an object not more to be desired than difficult to be obtained in a government wholly elective. The subjects of its jurisdiction are those offences which proceed from the misconduct of public men, or, in other words, from the abuse or violation of some public trust. They are of a nature which may with peculiar propriety be denominated POLITICAL, as they relate chiefly to injuries done immediately to the society itself. The prosecution of them, for this reason, will seldom fail to agitate the passions of the whole community, and to divide it into parties more or less friendly or inimical to the accused. In many cases it will connect itself with the pre-existing factions , and will enlist all their animosities, partialities, influence, and interest on one side or on the other; and in such cases there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.

The delicacy and magnitude of a trust so deeply concerns the political reputation of every man engaged in the administration of public affairs, speak for themselves. The difficulty of placing it rightly, in a government resting entirely on the basis of periodical elections, will be as readily perceived, when it is considered that the most conspicuous characters in it will, from that circumstance, be too often the leaders or the tools of the most cunning or the most numerous faction, and on this account can hardly be expected to possess the requisite neutrality towards those whose conduct may be the subject of scrutiny.

The convention, it appears, thought the Senate the most fit depositary of this important trust. Those who can best discern the intrinsic difficulty of the thing, will be least hasty in condemning that opinion, and will be most inclined to allow due weight to the arguments which may be supposed to have produced it (332,333)....