Saturday, October 14, 2017

George & Lizzie: A Novel by Nancy Pearl

Nancy Pearl, originally a librarian by trade, has written a number of nonfiction books that help people decide what to read. And she is the host of a television show, Book Lust with Nancy Pearl, where she interviews writers, and discusses their books with them. Now she has written her own novel. And it is not about the life of a librarian. Not even close!

By the looks of the front cover, you might think that the book is about a woman who had a whole lot of boyfriends. But you would be wrong. Lizzie, the main character in the book had only one true love in her life. And he left her and never came back.

The name of her true love is one of the names on the front cover of the book. But it isn't George. George was just the name of the guy that she married.

As for Maverick, Loren, Ranger, and all but one of the others, they were members of Lizzie's high school football team. They were part of the Great Game Lizzie played during her senior year in high school, a game she replayed in her mind for years on end....

Saturday, September 30, 2017

The Reckless Gamble in Our Electoral System

The results of the 2016 Presidential election were still weighing heavily on my mind when I first saw this book a few months ago. It was in the storage unit containing the remaining stock of books belonging to my friend George Spiero, who was finally retiring from the book business. The first paragraph on the front flap of the dust jacket immediately attracted my attention:

This book is essential reading for any United States citizen who wants to understand our present system of choosing a President and a Vice-President, the dangers inherent in it, and what urgently needs to be done to improve it.

James Michener wrote this book in 1969 after serving as an elector of the Pennsylvania Electoral College for the 1968 Presidential election between Richard Nixon, Hubert Humphrey and George Wallace. Michener believed that Wallace would win the South and all its electoral votes. And if neither Nixon or Humphrey attained 270 electoral votes, the election would go to the House of Representatives. Or not.

Wallace had other ideas. In what he called "a solemn covenant," Wallace intended to offer Nixon and Humphrey his electoral votes in exchange for certain concessions, one of which surely would be "abandonment of any type of civil rights legislation."

But Michener had an alternative plan. If neither Nixon or Humphrey attained 270 electoral votes, and if Humphrey won Pennsylvania, he was going to suggest to the other Pennsylvania delegates that they vote for Nixon instead, thus hopefully enabling Nixon to attain the 270 votes needed.

If, however, the Pennsylvania electoral votes weren't enough to make Nixon the President, the election would then have to go to the House. But Michener was going to talk the New York delegation into casting their votes for Nelson Rockefeller, making him the third candidate to be considered by the House instead of Wallace. And if necessary, Michener believed he could convince his Pennsylvania delegates to join the New York delegates in voting for Rockefeller. All these electoral concoctions, by the way, are perfectly legal under the Constitution. But they surely would have been challenged in the Supreme Court, thus delaying the selection of a President.

As it was, Richard Nixon won the 1968 election with 309 electoral votes, and what might have been never did happen. But the fact that the electoral scenario could have happened so disturbed Michener that he researched the history of the Electoral System and wrote a book about it. The book, btw, was reprinted by the Dial Press, an affiliate of Penguin Random House, in 2014, 2015, and in 2016 before the last election.

If you think the Electoral College maneuverings were a mess, the House system would have been a quagmire. The three candidates with the highest electoral votes would have moved to the House. And the House could have chosen anyone of the candidates to be the next President of the United States! Each of the 50 states had but one vote. And Michener points out a gross imbalance: Alaska, Nevada, Wyoming, and Vermont, with a total population of 1,467,000, according to 1968 estimates, would have four votes in choosing the President, and would outvote California, New York, and Pennsylvania, with a population of more than 49 million, but with only three votes (27).

In his book, Michener tells us about the genesis of the Electoral System and some of its flaws that became apparent as time went on. The system, according to Michener, was a compromise between large states and small states. One of the reasons the Founding Fathers had ruled out election solely by popular vote was because, as Eldridge Gerry of Massachusetts said, "The people are uninformed and would be led by a few designing men." There would still be a "popular vote," but the President would be elected, not by the total of the popular vote but by the vote of men in the electoral vote process who were knowledgable of the credentials of the candidates. Another reason (which Michener doesn't explicitly state in his book) that the Founding Fathers were against the popular vote was because smaller states were afraid that the larger states would elect their "favorite son."

Michener himself was involved in the election process in 1944 while stationed on Espiritu Santa, an island south of Guadalcanal. His commander received a directive from President Roosevelt's office that a proper election was to be held, and his commander appointed Michener to organize the vote on the island. Michener enlisted the aid of commercial artists and plastered the island with signs such as "Your Vote Is Your Freedom. Use It." Prior to the election, a representative from Washington visited the island and observed the voting preparations. The representative was visibly upset when he saw all the voting signs! "We want everyone to have the right to vote," he explained slowly. But we don't want them to vote." He didn't believe that the military troops on the island knew enough about the issues or the candidates to render knowledgeable votes. And he directed Michener to take down all the signs. Afterwards, the representative expressed his political philosophy to Michener, ending with the following statement:

He concluded with a statement I have never forgotten. 'I believe totally in democracy but I want to see great crowds at the polls in only one condition. When they are filled with blind fury at the mismanagement of the country and are determined to throw the bastards out. For the rest of the time I think you leave politics to those of us who really care."

Of the Electoral Plan of our Founding Fathers, James Michener had this to say:

I am surprised that this group of keen politicians and social philosophers should have failed to anticipate the two rocks on which their plan would founder. First, they did not foresee the rise of political parties or the way in which they would destroy the effectiveness of the electors. Second, they did not guess that the election by the House would work so poorly. This blindness on the part of the best leadership this nation has ever produced should give one pause if he thinks that in the next few years our current leadership will be able to come up with corrections that will end past abuses without introducing new. There could well be unforeseen weaknesses in our plans that would produce results just as unexpected as those which overtook the first great plan (72).Michener went on to say that "men of high principle" no longer met to decide who should lead the country. Instead, almost all of them voted the party line, with "winner take all."

Michener noted that polls taken in the 1960s showed that the general public was in favor of direct popular voting: 1966-63%; 1967-65%; 1968, before the election-79%; 1968, after the election-81%.

There were three times, prior to the publication of Michener's book, when a candidate won the popular vote, yet lost the election: 1824, 1876 and 1888. I will briefly address the 1876 election because it had the most radical effect on our nation.

Samuel J. Tilden was the Democratic candidate in the 1876 Presidential election. And his Republican opponent was Rutherford B. Hayes. Tilden won the popular vote by 251,746 votes, and reportedly won the electoral vote 204 to 165, with only 185 votes needed to win. But the Republicans questioned the validity of the electoral votes of four states: Florida 4, Louisiana 8, South Carolina 7, and Oregon 1(Oregon had three votes, but two votes cast for Hayes were unopposed). Two sets of electoral vote returns were submitted to Congress for each state, with some of the returns obviously fraudulent. As an aside, I'm not surprised that Florida had something to do with a stolen election....

A divided Congress, with the House ruled by Democrats and the Senate by Republicans, could not agree on how to go about electing a President under these circumstances. So they created an Electoral Commission consisting of members of the House, the Senate, and the Supreme Court. To make a long story short, the Democrats bungled the proceedings and the Commission chose Hayes to be the next President of the United States. The House, however, which rightfully held its own election as per the Constitution, had declared Tilden to be the President, and was prepared to nullify the vote of the Electoral Commission. But a compromise was reached: Hayes would be recognized as the winner of the 1876 election. In return, he would end Reconstruction governments in South Carolina and Louisiana and federal troops would be removed from all parts of the South.

This electoral compromise had a profound effect on the recent emancipation of the black population. Southern states were once again permitted to rule themselves. And the South rose again, with the Ku Klux Klan putting the black man back in his place, and glorifying the efforts of Confederate generals with monuments heralding their place in Southern Society.

In his book, Michener offers four proposals on how to improve our electoral system: the Automatic Plan, the District Plan, the Proportional Plan, and the Direct Popular Vote. All four proposals would require approval of a constitutional amendment: two-thirds of the House and Senate, and ratification by three-fourths of the States.

Under the Automatic Plan, the Electoral College would be abolished. The electoral votes would be counted the same as usual but would be sent directly to the Senate. Under several variations of the plan, House elections might be avoided. A candidate could win with 40% of the Electoral Vote under one plan, and in a run-off election in another.

Under the District Plan, the Electoral College would be retained. The electoral votes would be awarded by the popular vote in each district. eg. If a state had 38 districts, there would be 38 separate district electoral votes and not a winner-take-all electoral vote. If no candidate obtained 270 electoral votes, a joint session of Congress would elect the winner from the three top candidates. All Congressional members would have one vote.

Under the Proportional Plan, the Electoral College would be abolished. Electoral votes would be allocated, not by the winner-take-all system, but by allocating the proportional vote gained by each candidate. The winner would need 40% of the electoral votes, or a joint session of Congress would elect the winner from the top two candidates.

Under the Direct Popular Vote, the Electoral College would be abolished, electoral votes would not be allocated, and election by the House would not be necessary. The winner would be the candidate who won the most popular votes cast in the entire nation.

Michener provided appendixes displaying the relevant numbers for each electoral plan. But his last paragraph regarding the procedures of the electoral process as of 1969 still holds true today, 48 years later:

They must be abolished. They must be abolished now. They must be abolished before they wreck our democracy.

Heaven help us. The Electoral College was never abolished. And the winner of the 2016 Presidential Election is wrecking our democracy.

Donald J. Trump lost the popular vote by 2,865,075 votes, yet, by hook or by crook, he won the election because he had more electoral votes than Hillary Clinton. Recent events show that he is not "draining the swamp," or guiding our country through his great leadership–the greatest ever–in his opinion. Instead, he is making a mockery of the Presidency.

Yes. Our Founding Fathers were wary of the majority choosing a "favorite son." But they were also wary of the actions of factions.

By a faction, I understand a number of citizens, whether amounting to a majority or a minority of the whole, who are united and actuated by some common impulse of passion, or of interest, adverse to the rights of other citizens, or to the permanent or aggregate interests of the community.Trump's faction essentially hijacked the Republican Party. And by hook or by crook (Russian interference in our election, voter suppression, etc.), it gained enough electoral votes to win the election. One by one, Trump is tossing President Obama's achievements for the good of mankind out the window. And he is mismanaging our government.

James Madison The Federalist No. 10

If a faction consists of less than a majority, relief is supplied by the republican principle, which enables the majority to defeat the sinister views by regular vote. It may clog the administration, it may convulse the society, but it will be unable to execute and mask its violence under the forms of the Constitution.

James Madison, The Federalist No. 10

Unfortunately, the present forms of the Constitution has allowed a minority to exert its will over the majority, and to elect a President who clogs the administration with unqualified members of his administration, and who convulses the society every time he tweets. And that is the least of it!

If Michener were alive today, he would say, "it is time to amend our Constitution." And he would add, "it is time to throw the bastards out!"

Thursday, July 6, 2017

Tales from the Dodger Dugout by Carl Erskine

You don't have to be an old fan of the Brooklyn Bums to enjoy reading this book. In fact, you don't even have to be a baseball fan at all to enjoy reading this book. But if you are a baseball fan–and a fan of the old Brooklyn Dodgers at that–you will enjoy reading this book even more.

In this book, Carl Erskine tells 175 anecdotes about his teammates, rival players, managers, and even one about a Dodger batboy. He reminisces about the Yankee-Dodger rivalry, the Dodger-Giants rivalry, and about his teammates' acceptance of Jackie Robinson as the first black baseball player in the Major Leagues.

Not all the tales were from the Dodger dugout. One of them in particular came from the Polo Grounds bullpen on a rather memorable day for New York Giants fans. It was the ninth inning of the final game of the 1951 playoff series, and the Dodgers had a two-run lead. But the Giants had two men on base, and the potential winning run coming up to bat in the form of Bobby Thompson. Carl Erskine and Ralph Branca were warming up in the Polo Grounds bullpen for the Dodgers, and Charlie Dressen, the Dodger manager, called to see if his relievers were ready. "They're both ready," said Clyde Sukeforth, the bullpen coach; "However, Erskine is bouncing his overhead curve." So Dressen called for Branca. The rest is history. As for Erskine, whenever he was asked what his best pitch was, he would say, "The curveball I bounced in the Polo Grounds bullpen!"

Tuesday, June 20, 2017

The Card Catalog: Books, Cards and Literary Treasures by The Library of Congress. Reviewed by Jerry Morris

Every now and then there is a book that comes my way that I just can't put down. The Card Catalog is the latest one of them. Surrounding the book is a belly band displaying the LOC card catalog of Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. This is just one of over seventy images of LOC catalog cards displayed in this book. And on the opposite pages are images of the literary treasures the catalog cards identify. Interspersed among the images are sections detailing the history of the card catalog from its origin to its rise and fall.

Before there were card catalogs, there were several other methods used to catalog libraries, all of which are identified in this book, the earliest of which was a Sumerian cuneiform dating to around 2000 B.C. The Library of Congress wasn't the first library to use catalog cards but it advanced their use nationwide by providing copies of its own catalog cards to libraries across the country.

The last new card catalog was filed in the Main Reading Room of the Library of Congress on December 31, 1980, and the card cataloging system was declared "frozen," its use replaced by newer technology: the online catalog. This book, however, has its own card catalog inserted in a library pouch pasted on the front pastedown:

Moi Recommends!

Sunday, June 11, 2017

What Happened to Me:

My Life with Books, Research Libraries, and Performing Arts

by David H. Stam, Reviewed by Jerry Morris

My Life with Books, Research Libraries, and Performing Arts

by David H. Stam, Reviewed by Jerry Morris

"As is the wont of many old farts in retirement, I was reminiscing..."These are the author's words, not mine!

David H. Stam wrote those words in his Epilogue, "The Origins of this Screed." And in the very first paragraph of his Preface, Stam suggests that we go to this Epilogue near the back of the book "for more direct stimuli on the origins of these autobiographical memories." Now I am neither a slow reader or a speed reader, but that is the shortest time I ever got to Page 285 of any book!

In his Epilogue, David H. Stam was reminiscing to a friend about some events in his career when said friend suggested he write about his experiences. That was in 1998 – And in Beijing, of all places. It would take another ten years at least, and the urgings of a few more friends before Stam decided to write about his experiences. And he had a lot to write about; not only about himself, but about the many friends he met along the way in his many years of librarianship.

Here is where I, myself, diverted a bit. Instead of returning to the Preface, I proceeded from the Epilogue to Stam's Index – I sometimes browse the index of a book before reading it. When browsing Stam's Index, I recognized a number of names. His Index is a veritable Who's Who in the Library, Literary, and Book Arts Worlds.

In his forty years of library work, David H. Stam worked his way up from a clerk-typist position at the New York Public Library to positions in the upper echelons of library administration: at the New York Public Library, the Newberry Library, as well as at the libraries of Johns Hopkins University and Syracuse University.

David H. Stam devotes the first fifty-nine pages of his book to his family, his childhood, his schooling, and his two-year stint in the U. S. Navy as a journalist. As a child at his local library, Stam "resolved to read the entire library collection, starting with Dewey 001." And by his high school years, he fancied himself to be, in Coleridge's terms, a library cormorant: a voracious reader. Stam's career working with libraries actually began while he was still in the Navy. While his ship, the USS Galveston was being converted to a modern missile cruiser, Stam was put in charge of the ship's library of 3,000 volumes of books.

From page 60 on, Stam rambles on about his life with libraries, and about a few of his side interests. I found his book to be an interesting read for the most part. His subtitle: My Life with Books, Research Libraries, and Performing Arts, identifies two of the areas I found most interesting, with Performing Arts being the least interesting–nothing wrong with Performing Arts, mind you; it's just not my cup of tea.

Although the majority of his book pertains to matters of librarianship–and rightly so– Stam devotes a few pages to his life as a book collector (Yay!) and happens to mention his Polar Exploration Collection and his Leigh Hunt Collection. Moreover, Stam is a member of the Grolier Glub, and mentions the club no less than twelve times in his Index. And Stam and his wife Deirdre have enjoyed a long companionship with their friend, Terry Belanger, founder of the Rare Book School, and Stam reminisces about their friendship in his book as well.

What I appreciated most about David H. Stam's book, however, was his positioning of his footnotes on the pages they referred to, instead of at the back of the book, a sore point of mine. I would rather have the reference sources of the footnotes of related information readily available than have to flip to the back of the book and search for the references. And Lord help me if I wait until I finish reading the book before referring to the footnotes! I wouldn't remember what the footnotes were referring to in the first place! There! Rant over!

A surprising number of the references that Stam's footnotes referred to are available for reading online. Some of them require login access: eg: The Library of the Bibliographical Society, of which I am a member:

Other footnote references are available via Haithi Trust. eg: Bulletin of the NYPL Summer 1974:

Still other footnotes are available via JSTOR. eg:

I should mention that my copy of What Happened to Me... came from the author himself.

Being a Leigh Hunt collector, David noticed my April 27, 2017 post to My Sentimental Library blog, Leigh Hunt & Two Leigh Hunt Collectors: Joseph T. Fields & Luther A. Brewer, on the web, enjoyed reading it, and wrote to tell me about his own Leigh Hunt Collection. And what a collection it is!

Finally, David's selected publications are listed in Appendix II of his book. I have made use of this list to read his online articles and to acquire copies of available Leigh-Hunt-related publications. Now, it seems, I am starting a Leigh Hunt sub-collection: books containing articles by David H. Stam about Leigh Hunt!

Monday, February 13, 2017

Hubert's Freaks:

The Rare Book Dealer, The Times Square Talker, and the Lost Photos of Diane Arbus

by Gregory Gibson.

Reviewed and Commented Upon by Jerry Morris

The Rare Book Dealer, The Times Square Talker, and the Lost Photos of Diane Arbus

by Gregory Gibson.

Reviewed and Commented Upon by Jerry Morris

One might assume that the sale of the Hubert's material would be as twisted and difficult as the events leading to its discovery. In actuality, the process by which the archive came to market proceeded in such a straightforward and timely manner that it almost seems out of character with the rest of story (262).

Gregory Gibson 2008: the first paragraph of the last chapter of the hardback edition of Hubert's Freaks.

Hardback edition Paperback edition

I don't usually buy both the hardback edition and the paperback edition of a book. But I made an exception for Hubert's Freaks. I'll explain why after reviewing the hardback edition of the book.

Gregory Gibson uses the words twisted and difficult to describe the events leading to the discovery of the Hubert's archive. I shall add the word freakish because Hubert's Freaks has a rather freakish beginning.

In the Preface, the author tells us about the out-of-body experience of Bob Langmuir, the main character of the book. He was ejected from a vehicle on the same day the photographer Diane Arbus slit her wrists while soaking in her bathtub, the first of a number of coincidences. Throw in a man dressed all in blue and walking on crutches who retrieved a tire for Bob to sit in to ease his pain immediately after the accident, and you have either one freakish introduction–or maybe it was just a mere hallucination on the part of the main character, the bookseller Bob Langmuir. He didn't remember the details of the accident until years later when he freaked out while hitching a ride from a drunk driver on the Massachusetts Turnpike. And, mind you, this is just from the Preface!

Gregory Gibson knows how to weave a tale. He gives us some background on Hubert's Museum and its entertainers. Then he tells us a little bit about Diane Arbus, emphasizing that everyone pronounced her first name as Deeyan. Gibson doesn't re-introduce the main character Bob Langmuir until the fifth chapter of the book, which sounds bad, but it's really not because we're only on page 32 of the book.

It was an emotional roller coaster for Bob Langmuir for a while after that: deep depression, a rocky marriage, and nasty, prolonged divorce proceedings. By page 142 Bob had signed himself into a mental hospital. Prior to that, Bob had given up antiquarian bookselling and switched to the acquisition and sale of ephemeral material pertaining to African Americana. Bob had already acquired photos and documents of a Black sideshow from a so-called Nigerian prince named Okie. Bob's diligent research revealed that the photos were of the freaks of Hubert's Museum. And the photos were taken by Diane Arbus. Among the documents was a notebook of Charlie, the Times Square talker of Hubert's Museum. Meanwhile, Gregory Gibson is telling us more about Diane Arbus and her connection with Hubert's Museum, and the world of art.

Gregory Gibson begins Part Two of his book on Page 143, and titles it the New Bob. By page 156, Bob was out of the hospital and living with friends because his wife had a Protection From Abuse (PFA) order forbidding him to go anywhere near her. By page 159 Bob is moving in with a woman he met on the internet–not a bad thing at all because Bob and Renee are still together. And happy about it. Meanwhile, Bob is told that the Arbus photos need to be authenticated by the Arbus Estate, but the authentication process in no way proceeds in a straightforward and timely manner.

All the while, Bob is searching the web for additional ephemera relating to Arbus and freak shows, and African Americana, and comes across G. T. Boneyard, a Florida dealer who appeared to have the second half of the Hubert's archive, including five vintage photos possibly taken by Diane Arbus. Bob flew down to Florida and traded a sideshow collection for the material from Hubert's archive. But it took more than a day because G. T. Boneyard "had to sleep on it" before consenting to the deal.

We're now on page 185 and Gregory Gibson is filling us in on the life of Richard Charles Lucas, AKA Charlie, the Times Square talker, which takes up six pages. Bob shared the same initials as Richard Charles Lucas: R. C. L. which stands for Robert Cole Langmuir. Moreover, both Bob and Charlie shared the same birthday, August 15.

It would only take Gibson five pages to write about it, but it took an entire year for the authentication process of the Arbus photos Bob acquired from the Nigerian prince Okie to be completed by the Arbus Estate. Diane Arbus's daughter Doone did it, and she did a sloppy job of it, authenticating one of the Arbus photos twice. Of the twenty-nine photos, Doone authenticated twenty-two of them from the negatives in the Arbus Estate's files. And Bob still had to get the five Arbus photos he acquired from Boneyard authenticated.

A whirlwind of action and inaction occurs in the next sixty plus pages, or over two years of real time. Bob's divorce proceedings dragged on; the judge ruled the Arbus archive to be part of the estate. The agreed-upon stipulated value of the Arbus archive was $250,000, which was the estimate previously given sight unseen by Sotheby's. Bob's wife then fires her third lawyer and her fourth lawyer suggests a settlement that is agreeable to both parties. And surprisingly, the Arbus archive was not a part of the divorce settlement. The on-again-off-again dealings for a sale of the Hubert's archive and Diana Arbus photos to the Metropolitan Museum of Art dragged on. And finally, Steve Turner, an old friend of Bob's, worked out a deal with Philips de Pury and Company to sell the Arbus photos at auction. The auction was to take place in April 2008. The experts at Philips de Pury expected the selling price of the photos to exceed a "life-altering sum." Gregory Gibson didn't think the money would change Bob; "he had already changed."

And that's how the hardback edition of Hubert's Freaks ended...

"What the hell?

I wanted to know how much Bob got for the Arbus photos!

I learned from one of Gregory Gibson's blog posts that Bob eventually sold the collection to a major New York institution. But Gibson didn't state how much Bob got for the photos! So I emailed Gregory Gibson. And that's when I learned that the publication of the hardback edition was timed to coincide with the auction. Moreover, the paperback edition included an AFTERWORD that contained new information about the sale of the Hubert's archive.

AFTERWORD

By no means did the process by which the Hubert's archive came to market proceed in the straightforward and timely manner as expressed by Gregory Gibson in the first paragraph of the last chapter of the hardback edition of Hubert's Freaks. And Bob Langmuir's old friend Steve Turner was partly to blame.

Steve Turner scored a publicity coup of sorts, getting the New York Times to write a detailed story about Bob Langmuir's discovery of the Hubert's archive and the Arbus photos. Gibson's upcoming book, Hubert's Freaks, was mentioned in the article, as was the Philips de Pury auction itself, scheduled for April 8, 2008. But the New York Times article was published on November 22, 2007. In the AFTERWORD of the paperback edition, Gregory Gibson stated that the article "had come out far too early... Gibson's publishers groaned... Events proved them correct, but that wasn't the worst of it."

One of the people who read the New York Times article was Bayo Ogunsanya, the Nigerian prince called "Okie" in Gibson's book. A March 6, 2008 story in the New York Daily News depicted how Okie was "tricked" into selling the Diane Arbus photos for $3500, even though Bob Langmuir knew they were worth much more. Okie filed a lawsuit to stop the sale of the Hubert's archive.

When Philips de Pury cancelled the auction, they claimed that a buyer for the entire archive had come forward. But most people believed that Okie's lawsuit had something to do with the cancellation of the auction. Gregory Gibson, however, thought otherwise, and expressed as much in his AFTERWORD.

Gibson believed that Philips de Pury cancelled the auction because they realized the auction was too much of a monetary risk. The day before the Philip's auction was to be conducted, Sotheby's conducted the sale of the Quillan collection of nineteenth and twentieth century images, bringing $9 million in sales. Moreover, Christie's had two sales coming up a few days after the scheduled Philips auction, one of which included a collection of 50 Arbus photos. Philips de Pury realized that their timing was poor and that they couldn't compete with the two major auction houses, so they cancelled their auction. Probably a wise move: the sales of the two Christie's auctions totaled $5.5 million.

As the paperback edition of Hubert's Freaks went to press, Okie's lawsuit was still pending; a movie version of Hubert's Freaks fell through; the fake buyer never appeared; and Russia's largest luxury retail company, Mercury Group, purchased Philips de Pury, leaving Bob Langmuir having to deal with the Russians. Gregory Gibson was still hopeful that the story would have a happy ending, while Bob, with surprising tranquility considering the circumstances, went on with his life, spending a lot of time in Mexico. And that's how the paperback edition of Hubert's Freaks ended.

There is an epilogue to this story, revealed to me by both Gregory Gibson and Bob Langmuir. Okie's lawsuit was settled out of court in March 2009. And the New York Public Library bought the Hubert's archive for an undisclosed amount of money. But between settling Okie's lawsuit and paying all the lawyer fees, Bob got nothing but heartache from the sale of the Hubert's archives.

There is, however, a happy ending to the story.

During all the trials and tribulations of the Hubert's archives dealings, Bob pressed on and continued to acquire African Americana. And in July 2009 he sold the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection to Emory University for a life-altering sum.

You can browse the photographs of the collection via the Emory Digital Gallery.

At the time of this blog post writing, The Atlanta Black Star still carries Rosalind Bentley's eloquent article about the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection. The article first appeared in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution the day before on July 8, 2012.

And on his Bookman's Log blog on July 16, 2012 Gregory Gibson posted "Extreme Book Selling," a post which recaps Bob Langmuir's meticulous research of the Hubert's archives, and congratulates him on the sale of the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection to Emory University.

And Bob is building a new archive...

In the Preface, the author tells us about the out-of-body experience of Bob Langmuir, the main character of the book. He was ejected from a vehicle on the same day the photographer Diane Arbus slit her wrists while soaking in her bathtub, the first of a number of coincidences. Throw in a man dressed all in blue and walking on crutches who retrieved a tire for Bob to sit in to ease his pain immediately after the accident, and you have either one freakish introduction–or maybe it was just a mere hallucination on the part of the main character, the bookseller Bob Langmuir. He didn't remember the details of the accident until years later when he freaked out while hitching a ride from a drunk driver on the Massachusetts Turnpike. And, mind you, this is just from the Preface!

Gregory Gibson knows how to weave a tale. He gives us some background on Hubert's Museum and its entertainers. Then he tells us a little bit about Diane Arbus, emphasizing that everyone pronounced her first name as Deeyan. Gibson doesn't re-introduce the main character Bob Langmuir until the fifth chapter of the book, which sounds bad, but it's really not because we're only on page 32 of the book.

It was an emotional roller coaster for Bob Langmuir for a while after that: deep depression, a rocky marriage, and nasty, prolonged divorce proceedings. By page 142 Bob had signed himself into a mental hospital. Prior to that, Bob had given up antiquarian bookselling and switched to the acquisition and sale of ephemeral material pertaining to African Americana. Bob had already acquired photos and documents of a Black sideshow from a so-called Nigerian prince named Okie. Bob's diligent research revealed that the photos were of the freaks of Hubert's Museum. And the photos were taken by Diane Arbus. Among the documents was a notebook of Charlie, the Times Square talker of Hubert's Museum. Meanwhile, Gregory Gibson is telling us more about Diane Arbus and her connection with Hubert's Museum, and the world of art.

Gregory Gibson begins Part Two of his book on Page 143, and titles it the New Bob. By page 156, Bob was out of the hospital and living with friends because his wife had a Protection From Abuse (PFA) order forbidding him to go anywhere near her. By page 159 Bob is moving in with a woman he met on the internet–not a bad thing at all because Bob and Renee are still together. And happy about it. Meanwhile, Bob is told that the Arbus photos need to be authenticated by the Arbus Estate, but the authentication process in no way proceeds in a straightforward and timely manner.

All the while, Bob is searching the web for additional ephemera relating to Arbus and freak shows, and African Americana, and comes across G. T. Boneyard, a Florida dealer who appeared to have the second half of the Hubert's archive, including five vintage photos possibly taken by Diane Arbus. Bob flew down to Florida and traded a sideshow collection for the material from Hubert's archive. But it took more than a day because G. T. Boneyard "had to sleep on it" before consenting to the deal.

We're now on page 185 and Gregory Gibson is filling us in on the life of Richard Charles Lucas, AKA Charlie, the Times Square talker, which takes up six pages. Bob shared the same initials as Richard Charles Lucas: R. C. L. which stands for Robert Cole Langmuir. Moreover, both Bob and Charlie shared the same birthday, August 15.

It would only take Gibson five pages to write about it, but it took an entire year for the authentication process of the Arbus photos Bob acquired from the Nigerian prince Okie to be completed by the Arbus Estate. Diane Arbus's daughter Doone did it, and she did a sloppy job of it, authenticating one of the Arbus photos twice. Of the twenty-nine photos, Doone authenticated twenty-two of them from the negatives in the Arbus Estate's files. And Bob still had to get the five Arbus photos he acquired from Boneyard authenticated.

A whirlwind of action and inaction occurs in the next sixty plus pages, or over two years of real time. Bob's divorce proceedings dragged on; the judge ruled the Arbus archive to be part of the estate. The agreed-upon stipulated value of the Arbus archive was $250,000, which was the estimate previously given sight unseen by Sotheby's. Bob's wife then fires her third lawyer and her fourth lawyer suggests a settlement that is agreeable to both parties. And surprisingly, the Arbus archive was not a part of the divorce settlement. The on-again-off-again dealings for a sale of the Hubert's archive and Diana Arbus photos to the Metropolitan Museum of Art dragged on. And finally, Steve Turner, an old friend of Bob's, worked out a deal with Philips de Pury and Company to sell the Arbus photos at auction. The auction was to take place in April 2008. The experts at Philips de Pury expected the selling price of the photos to exceed a "life-altering sum." Gregory Gibson didn't think the money would change Bob; "he had already changed."

And that's how the hardback edition of Hubert's Freaks ended...

"What the hell?

I wanted to know how much Bob got for the Arbus photos!

I learned from one of Gregory Gibson's blog posts that Bob eventually sold the collection to a major New York institution. But Gibson didn't state how much Bob got for the photos! So I emailed Gregory Gibson. And that's when I learned that the publication of the hardback edition was timed to coincide with the auction. Moreover, the paperback edition included an AFTERWORD that contained new information about the sale of the Hubert's archive.

Bob traveled to Manhattan on April 7, 2008, with a light heart and high hopes, fully expecting to come home a millionaire. He woke on April 8 to learn that Philips de Pury & Company had canceled the auction of the Hubert's archive overnight and without warning (265).

Gregory Gibson 2009 The first paragraph of the AFTERWORD in the paperback edition.

By no means did the process by which the Hubert's archive came to market proceed in the straightforward and timely manner as expressed by Gregory Gibson in the first paragraph of the last chapter of the hardback edition of Hubert's Freaks. And Bob Langmuir's old friend Steve Turner was partly to blame.

Steve Turner scored a publicity coup of sorts, getting the New York Times to write a detailed story about Bob Langmuir's discovery of the Hubert's archive and the Arbus photos. Gibson's upcoming book, Hubert's Freaks, was mentioned in the article, as was the Philips de Pury auction itself, scheduled for April 8, 2008. But the New York Times article was published on November 22, 2007. In the AFTERWORD of the paperback edition, Gregory Gibson stated that the article "had come out far too early... Gibson's publishers groaned... Events proved them correct, but that wasn't the worst of it."

One of the people who read the New York Times article was Bayo Ogunsanya, the Nigerian prince called "Okie" in Gibson's book. A March 6, 2008 story in the New York Daily News depicted how Okie was "tricked" into selling the Diane Arbus photos for $3500, even though Bob Langmuir knew they were worth much more. Okie filed a lawsuit to stop the sale of the Hubert's archive.

When Philips de Pury cancelled the auction, they claimed that a buyer for the entire archive had come forward. But most people believed that Okie's lawsuit had something to do with the cancellation of the auction. Gregory Gibson, however, thought otherwise, and expressed as much in his AFTERWORD.

Gibson believed that Philips de Pury cancelled the auction because they realized the auction was too much of a monetary risk. The day before the Philip's auction was to be conducted, Sotheby's conducted the sale of the Quillan collection of nineteenth and twentieth century images, bringing $9 million in sales. Moreover, Christie's had two sales coming up a few days after the scheduled Philips auction, one of which included a collection of 50 Arbus photos. Philips de Pury realized that their timing was poor and that they couldn't compete with the two major auction houses, so they cancelled their auction. Probably a wise move: the sales of the two Christie's auctions totaled $5.5 million.

As the paperback edition of Hubert's Freaks went to press, Okie's lawsuit was still pending; a movie version of Hubert's Freaks fell through; the fake buyer never appeared; and Russia's largest luxury retail company, Mercury Group, purchased Philips de Pury, leaving Bob Langmuir having to deal with the Russians. Gregory Gibson was still hopeful that the story would have a happy ending, while Bob, with surprising tranquility considering the circumstances, went on with his life, spending a lot of time in Mexico. And that's how the paperback edition of Hubert's Freaks ended.

There is an epilogue to this story, revealed to me by both Gregory Gibson and Bob Langmuir. Okie's lawsuit was settled out of court in March 2009. And the New York Public Library bought the Hubert's archive for an undisclosed amount of money. But between settling Okie's lawsuit and paying all the lawyer fees, Bob got nothing but heartache from the sale of the Hubert's archives.

There is, however, a happy ending to the story.

During all the trials and tribulations of the Hubert's archives dealings, Bob pressed on and continued to acquire African Americana. And in July 2009 he sold the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection to Emory University for a life-altering sum.

You can browse the photographs of the collection via the Emory Digital Gallery.

At the time of this blog post writing, The Atlanta Black Star still carries Rosalind Bentley's eloquent article about the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection. The article first appeared in the Atlanta Journal-Constitution the day before on July 8, 2012.

And on his Bookman's Log blog on July 16, 2012 Gregory Gibson posted "Extreme Book Selling," a post which recaps Bob Langmuir's meticulous research of the Hubert's archives, and congratulates him on the sale of the Robert Langmuir African American Photograph Collection to Emory University.

And Bob is building a new archive...

Friday, November 25, 2016

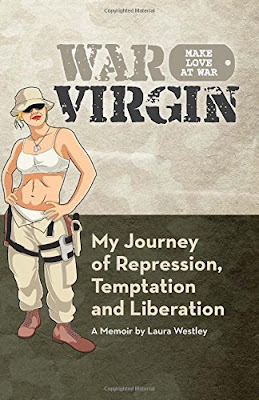

War Virgin: My Journey of Repression, Temptation and Liberation.

A Memoir by Laura Westley

Reviewed by Jerry Morris

A Memoir by Laura Westley

Reviewed by Jerry Morris

Poets and playwrights have been writing about virgins for centuries. But until now, I don't think anyone has written about being a virgin in a military environment, battling not only the enemy, but battling virginity itself.

I guarantee you that Laura Westley will grab your attention on the very first page of her memoir. You may be shocked. You may be amused. But you will want to turn the page to see what the hell this woman, this virgin, is going to do next. She is upfront, in your face, and very personal in revealing her experiences as a virgin in the military.

Throw in growing up with a demeaning father, completing four demanding years of soldierly at West Point, and serving a combat tour in Iraq during Iraqi Freedom, and you have the makings for an interesting memoir. Sprinkle in some humor, some sadness, some unpleasantness, and a whole lot of foreplay, and you have a book that you won't be able to put down. And if you still haven't gotten enough, there is also War Virgin, the Play.

My wife and daughter saw the play, while I watched the grandchildren. Before seeing the play, my daughter read the book from cover to cover nonstop, continuing on while her children slept. Before the book was published, and before my wife saw the play, my wife listened to Laura Westley speak at a political luncheon. Afterwards, she "suggested" I invite Laura Westley to be guest speaker at a meeting of the Florida Bibliophile Society (I'm the VP). I know when to take orders. So on June 6, 2016, I cordially invited Laura Westley to be our guest speaker during National Women's History Month in 2017. And she readily accepted our invitation.

Laura Westley, author and playwright of War Virgin, will be the keynote speaker at the meeting of the Florida Bibliophile Society at 1:30 pm on Sunday March 19, 2017 at the Seminole Community Library, 9200 113th St. North, Seminole, Florida, 33772 Admission is free. But just a word of advice: don't bring your Sunday School teacher with you!

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

Boswell's Books:

Four Generations of Collecting and Collectors

by Terry Seymour

and commented upon by Jerry Morris

Four Generations of Collecting and Collectors

by Terry Seymour

and commented upon by Jerry Morris

Samuel Johnson once instructed James Boswell (1740-1795) to surround himself with books. And at Auchinleck, James Boswell surrounded himself with books acquired by his grandfather James Boswell (1672-1749), by his father Lord Auchinleck (1706-1782), and by books that he himself acquired. And after his death, his sons Sir Alexander Boswell (Sandy) (1755-1822) and James Boswell the Younger (Jamie)(1778-1822) added a few thousand more books to the Auchinleck Library. And now, with Boswell's Books, Terry Seymour provides an extensive book-by-book reconstruction of the Boswell Library.

Yes, that's Samuel Johnson raising a folio above his head in the cover photo above. But that's not the bookseller Thomas Osborne who is about to be bashed. It is Lord Auchinleck. And that is James Boswell himself cringing in the background. The etching, "The Contest at Auchinleck," and part of Rowlandson's 1786 Picturesque Beauties of Boswell, offers a contemporary view of the Auchinleck Library.

I am well acquainted with the books in the Auchinleck Library. While Terry Seymour was researching, cataloguing, and gathering information for his book, I was leading a parallel cataloguing project on the social media website, Library Thing: the online cataloguing of the library of James Boswell. And Terry Seymour was one of our Auchinleck Advisers.

James Caudle, the Associate Editor of the Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell, was Terry Seymour's primary adviser for his book. In fact, he is the author of the preface of Terry Seymour's book. And he was the primary adviser and chief supplier of catalogues for the Boswell Cataloguing Team on Library Thing.

The Boswell Cataloguing Team began cataloging the Boswell Library in October 2008. And we completed our cataloguing in August 2012. But in June 2013, thanks to an article by Terry Seymour in the March 2013 issue of the Johnsonian News Letter, "An Appendix to Boswell's Books," I was recataloguing the 1810 Catalogue of Greek & Latin Classics in the Auchinleck Library; I was adding eleven items I had somehow missed two years earlier.

Terry Seymour began his Boswell project sometime in 2009. And his book was published in April 2016. I received my copy on April 20th. Terry said I was the first collector to receive an ordered copy. I had volunteered beforehand to be a reviewer (to get a free copy), but Terry believed–and rightfully so–that my name and the name of Library Thing were mentioned too many times in his book for me to write a fair and impartial review. What I can do, however, is tell you a little bit about both cataloguing projects.

The purpose of the Library Thing Catalogue of James Boswell was to provide online access to the individual listings of books formerly owned by James Boswell and his family.

The purpose of Boswell's Books, as stated by the author, "is to present a complete picture of the known history of each book, from the time it entered the Boswell family library until the present day."

The Library Thing Cataloguing Team began by cataloguing books listed in the 1825 Action Catalogue, and then those books listed in the 1893 Auchinleck Catalogue. Most of the books in the 1825 catalogue were formerly owned by Jamie Boswell. And most of the books in the 1893 catalogue were formerly owned by Lord Auchinleck. The cataloguing team then catalogued the books listed in the 1810 Catalogue of Greek & Latin Classics in the Auchinleck Library, the 1916 James Boswell Talbot Sale, the 1917 Dowell Sale, the Circa 1770 Catalogue of Books Belonging to James Boswell, and Curious Productions, a collection of chapbooks James Boswell acquired in 1763.

The 1810 Catalogue contained Greek and Latin books that Sandy Boswell inherited from his father, and Sandy was the cataloguer. James Boswell himself was the cataloguer of what I cite as the "Circe 1770 Catalogue." Terry Seymour cites it as the "JB Handlist" c1771. The 1916 sale contained items that were not listed in the 1893 auction. The auctioneers of the 1917 sale combined remainders from the Auchinleck library with items from other libraries.

Terry Seymour's catalogue, Boswell's Books, contains not only the books, but also the manuscripts that are listed in the above catalogues, but with one exception. The 1825 Catalogue contained a number of Jamie Boswell's books that were formerly owned by Edmond Malone. And Terry Seymour catalogued only those "books that have a direct bearing on their Boswell owners."

Terry Seymour referenced a number of additional sources when he catalogued the books and manuscripts listed in Boswell's Books: Margaret Montgomerie Boswell's Inventory of the Auchinleck Library 1783-1785, Sandy Boswell's Catalogue of the Manuscripts at Auchinleck 1808-1809, fragments of Sandy Boswell's Catalogue of the Auchinleck Library 1803-1810, the Walpole Galleries Sale of 1920, and the 1976 Family Sale. Terry Seymour also listed presentation copies given by the Boswells to their friends.

Margaret Montgomerie Boswell was James Boswell's wife. And shortly after Lord Auchinleck's death, she catalogued the books and manuscripts as they appeared on the shelves in the Auchinleck Library, identifying the books by the titles on their spines. The first part of the catalogue, however, is missing.

Sandy Boswell's catalogue of the manuscripts identified 89 manuscripts in the Auchinleck Library. Terry thinks it is likely that this catalogue was intended to be part of Sandy's General Catalogue, of which no complete copy exists.

Terry Seymour says that the 1920 Walpole Sale included more books with Boswell ownership marks than any other source. And the identity of the prior owner remains unknown, and also how the owner acquired the books. Of the 400 lots listed in this sale, only 12 lots appear in any other source. As for the 1976 sale, Terry Seymour notes only two books of merit in the sale.

By far, the greatest accomplishment of Boswell's Books, in my opinion, is Terry Seymour's identification of many of the 436 items sold in the 1893 Auchinleck Sale that were not identified by title in the auction catalogue. These books were tabulated under the dreadful phrases of and others and and another. Terry Seymour searched high and low and acquired the contemporary bookseller catalogues of the three biggest buyers of the 1893 Auchinleck Sale: Bernard Quaritch, William Ridler, and Pickering and Chatto. Using these and other contemporary bookseller catalogues he acquired, he identified many of the and others of the 1893 Auchinleck Sale.

I will reveal here, particularly for those Boswellians and scholars residing in the state of Florida, and for those booklovers who want to know more about the Boswell Library and Boswell's Books, that Terry Seymour will be the guest speaker at the January 15, 2017 meeting of the Florida Bibliophile Society.

Both Boswell's Books and the Boswell Library Thing Catalogue should be required references for university libraries. Boswell's Books more so because, where possible, Terry Seymour has traced the provenance of the books down to their current location– "if" they are recorded in library databases. And that is a big IF...

I call to mind Nicholson Baker's article, "Discards," from his book, The Size of Thoughts." This article, which first appeared in The New Yorker, detailed the initial conversion of library data from library cards to online library catalogues in the 1980s and 1990s. At most libraries, only the bibliographical information on the front of the library card was transferred. And when the library card was discarded, the provenance information, if recorded on the verso of the card, disappeared.

Here's the synopsis of Baker's article, which appeared below the title, DISCARDS, in the April 4, 1994 issue of The New Yorker:

Yes, that's Samuel Johnson raising a folio above his head in the cover photo above. But that's not the bookseller Thomas Osborne who is about to be bashed. It is Lord Auchinleck. And that is James Boswell himself cringing in the background. The etching, "The Contest at Auchinleck," and part of Rowlandson's 1786 Picturesque Beauties of Boswell, offers a contemporary view of the Auchinleck Library.

I am well acquainted with the books in the Auchinleck Library. While Terry Seymour was researching, cataloguing, and gathering information for his book, I was leading a parallel cataloguing project on the social media website, Library Thing: the online cataloguing of the library of James Boswell. And Terry Seymour was one of our Auchinleck Advisers.

James Caudle, the Associate Editor of the Yale Editions of the Private Papers of James Boswell, was Terry Seymour's primary adviser for his book. In fact, he is the author of the preface of Terry Seymour's book. And he was the primary adviser and chief supplier of catalogues for the Boswell Cataloguing Team on Library Thing.

The Boswell Cataloguing Team began cataloging the Boswell Library in October 2008. And we completed our cataloguing in August 2012. But in June 2013, thanks to an article by Terry Seymour in the March 2013 issue of the Johnsonian News Letter, "An Appendix to Boswell's Books," I was recataloguing the 1810 Catalogue of Greek & Latin Classics in the Auchinleck Library; I was adding eleven items I had somehow missed two years earlier.

Terry Seymour began his Boswell project sometime in 2009. And his book was published in April 2016. I received my copy on April 20th. Terry said I was the first collector to receive an ordered copy. I had volunteered beforehand to be a reviewer (to get a free copy), but Terry believed–and rightfully so–that my name and the name of Library Thing were mentioned too many times in his book for me to write a fair and impartial review. What I can do, however, is tell you a little bit about both cataloguing projects.

The purpose of the Library Thing Catalogue of James Boswell was to provide online access to the individual listings of books formerly owned by James Boswell and his family.

The purpose of Boswell's Books, as stated by the author, "is to present a complete picture of the known history of each book, from the time it entered the Boswell family library until the present day."

The Library Thing Cataloguing Team began by cataloguing books listed in the 1825 Action Catalogue, and then those books listed in the 1893 Auchinleck Catalogue. Most of the books in the 1825 catalogue were formerly owned by Jamie Boswell. And most of the books in the 1893 catalogue were formerly owned by Lord Auchinleck. The cataloguing team then catalogued the books listed in the 1810 Catalogue of Greek & Latin Classics in the Auchinleck Library, the 1916 James Boswell Talbot Sale, the 1917 Dowell Sale, the Circa 1770 Catalogue of Books Belonging to James Boswell, and Curious Productions, a collection of chapbooks James Boswell acquired in 1763.

The 1810 Catalogue contained Greek and Latin books that Sandy Boswell inherited from his father, and Sandy was the cataloguer. James Boswell himself was the cataloguer of what I cite as the "Circe 1770 Catalogue." Terry Seymour cites it as the "JB Handlist" c1771. The 1916 sale contained items that were not listed in the 1893 auction. The auctioneers of the 1917 sale combined remainders from the Auchinleck library with items from other libraries.

Terry Seymour's catalogue, Boswell's Books, contains not only the books, but also the manuscripts that are listed in the above catalogues, but with one exception. The 1825 Catalogue contained a number of Jamie Boswell's books that were formerly owned by Edmond Malone. And Terry Seymour catalogued only those "books that have a direct bearing on their Boswell owners."

Terry Seymour referenced a number of additional sources when he catalogued the books and manuscripts listed in Boswell's Books: Margaret Montgomerie Boswell's Inventory of the Auchinleck Library 1783-1785, Sandy Boswell's Catalogue of the Manuscripts at Auchinleck 1808-1809, fragments of Sandy Boswell's Catalogue of the Auchinleck Library 1803-1810, the Walpole Galleries Sale of 1920, and the 1976 Family Sale. Terry Seymour also listed presentation copies given by the Boswells to their friends.

Margaret Montgomerie Boswell was James Boswell's wife. And shortly after Lord Auchinleck's death, she catalogued the books and manuscripts as they appeared on the shelves in the Auchinleck Library, identifying the books by the titles on their spines. The first part of the catalogue, however, is missing.

Sandy Boswell's catalogue of the manuscripts identified 89 manuscripts in the Auchinleck Library. Terry thinks it is likely that this catalogue was intended to be part of Sandy's General Catalogue, of which no complete copy exists.

Terry Seymour says that the 1920 Walpole Sale included more books with Boswell ownership marks than any other source. And the identity of the prior owner remains unknown, and also how the owner acquired the books. Of the 400 lots listed in this sale, only 12 lots appear in any other source. As for the 1976 sale, Terry Seymour notes only two books of merit in the sale.

By far, the greatest accomplishment of Boswell's Books, in my opinion, is Terry Seymour's identification of many of the 436 items sold in the 1893 Auchinleck Sale that were not identified by title in the auction catalogue. These books were tabulated under the dreadful phrases of and others and and another. Terry Seymour searched high and low and acquired the contemporary bookseller catalogues of the three biggest buyers of the 1893 Auchinleck Sale: Bernard Quaritch, William Ridler, and Pickering and Chatto. Using these and other contemporary bookseller catalogues he acquired, he identified many of the and others of the 1893 Auchinleck Sale.

I will reveal here, particularly for those Boswellians and scholars residing in the state of Florida, and for those booklovers who want to know more about the Boswell Library and Boswell's Books, that Terry Seymour will be the guest speaker at the January 15, 2017 meeting of the Florida Bibliophile Society.

Both Boswell's Books and the Boswell Library Thing Catalogue should be required references for university libraries. Boswell's Books more so because, where possible, Terry Seymour has traced the provenance of the books down to their current location– "if" they are recorded in library databases. And that is a big IF...

I call to mind Nicholson Baker's article, "Discards," from his book, The Size of Thoughts." This article, which first appeared in The New Yorker, detailed the initial conversion of library data from library cards to online library catalogues in the 1980s and 1990s. At most libraries, only the bibliographical information on the front of the library card was transferred. And when the library card was discarded, the provenance information, if recorded on the verso of the card, disappeared.

Here's the synopsis of Baker's article, which appeared below the title, DISCARDS, in the April 4, 1994 issue of The New Yorker:

America's great libraries are scrapping the card catalogue in favor of the more accessible on-line system, and many librarians are toasting the demise of the dog-eared file card and the bookish image it projects. But are they destroying their most important––and irreplaceable––contribution to scholarship?Now in many libraries, Special Collections has either retained or restored provenance information. But I wonder how many libraries have Boswell books in their library stacks that they no longer know about?

Monday, August 8, 2016

The Toad

by Elise Gravel

Reviewed by Jerry Morris

by Elise Gravel

Reviewed by Jerry Morris

I'm slowly adding a shelf or two of children's books in my library for my grandchildren to read when they visit. But I may have trouble keeping this book in my library. My wife believes at least one of the grandchildren will want to do a book report on it.

The Toad is part of a series of books by Elise Gravel about Disgusting Critters. And I do mean disgusting! Just look at the titles: The Worm, The Fly, Head Lice, The Slug, The Rat, The Spider, and The Toad!.

But kids don't find these critters to be disgusting. And Elise Gravel presents the toad as friendly and useful for the environment. And she adds a little humor in the book, which will make my granddaughters laugh. One of them will even say, "Again..."

I may have to get most of the other books in the series for my library–except for the book about head lice! That would make me scratch my head!

Moi recommends!

Wednesday, July 20, 2016

A Scout's Report: My 70 Years in Baseball

by George Genovese with Dan Taylor.

Reviewed by Jerry Morris

by George Genovese with Dan Taylor.

Reviewed by Jerry Morris

I loved playing baseball as a kid. I loved watching my kids play baseball. I loved umpiring baseball games: Little League, Pony League, High School, Mexican League. I love watching baseball games on TV. I love going to baseball games. And I love reading books about baseball.

This book, A Scout's Report: My 70 Years in Baseball, is one of the better ones. From Page 1 to page 244, you will witness George Genovese reliving and breathing baseball, first as a player, then as a manger, but mostly as a baseball scout. 44 of the players George Genovese signed became major leaguers and, when you read his book, you will find out which ones went on to become stars.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)